New Broke City

A series of fictional artist biographies created for New Broke City: a Celebration of Young and Broke Artists, a group show at the Studio 303 Gallery in New York, NY.

Using friends as photographic references, each piece consists of an ink and brush portrait alongside a fictional artist bio. As a group, these stories explore the relationship between art and identity, as well as ideas about audience, visibility, success and failure.

Erin

In the park, Erin wrote self-reflexive poems on fallen leaves, simple prose about loss and mutability. She did this week after week, year after year, repeating the same poem on hundreds of leaves or sometimes penning an inspired piece on the spot.

As it was, almost no one would read them. Occasionally a small child would come across the carefully incised script, but being unable to read or make sense of the message, the leaf was simply perceived as a beautiful anomaly of nature and soon discarded. The rest of her poem-leaves were overlooked, trampled, or scattered to the wind.

She persisted.

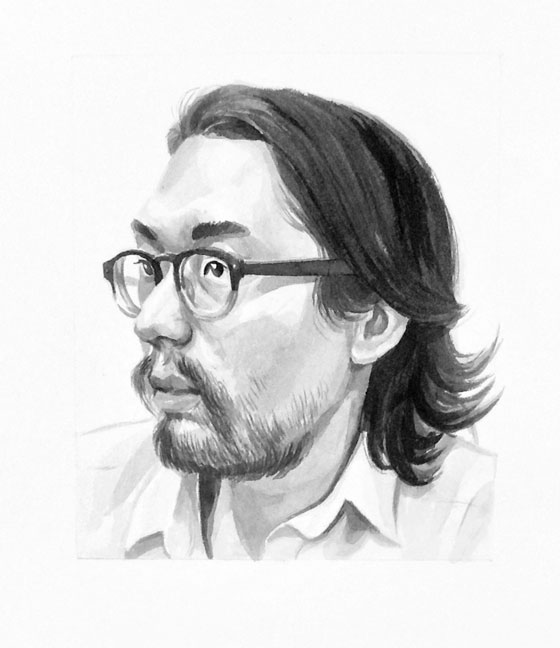

Arnold

Arnold wrote short stories whose characters bore an uncanny alliterative similarity to the names of his friends. As this and other resemblances came to light – tantalizing personal details and remarks told in private, now laid bare for New York’s literati – Arnold found his peer group quietly diminishing. At first it was unreturned phone calls, then lowered glances on the street, and finally the awkward, online de-friendship. His next published piece will be entitled, “Those Fucking Bastards, Who Needs Them Anyway.”

Samuel K.

Samuel K. took thriftstore paintings and re-purposed them in elaborate installation projects, entire domestic settings which he built from the walls up if he had to. Like most of the other components, the paintings were worked over or altered with raw substances, tar and wax, dirt and sand, so that the whole scene took on the resemblance of an evacuation site or an abandoned home.

Although he did not tell anyone, his mother had been an amateur painter so it grieved him privately to erase the precious, amber-hued landscapes and clumsy portraits. As a child, he revered the small, delicate still-lifes she produced in her ‘workshop,’ as she called it, which was really nothing more than the unused guest bedroom on the east side of the house. It had glorious morning light and here she spent time alone, or with Samuel staring in half-asleep from the hallway door. She painted briskly, mannerly, for about 45 minutes, then began to prepare the family’s breakfast, or did the wash, or ran into town to complete some errands. He loved the quietness of the paintings, but also the solitude this practice had allotted her, this time-away-from-time.

She was a clear-minded, dutiful woman, though Samuel suspected, as he grew older, that she imagined another life for herself. When he announced his intentions to make and study art she posed the standard questions about financial practicality, but seemed pleased with his decision nevertheless. She passed away a few years later and the house of his childhood was sold off.

Recently, he decided to recreate his mother’s workshop, plastered, dipped in tar, though not with her original paintings – these would be substituted by mostly unsigned, undated amateur works. Some bore simple inscriptions on their backs: “The Poconos, 1958;” “To Ada, my favorite niece;” but these would be unviewable to the general public.

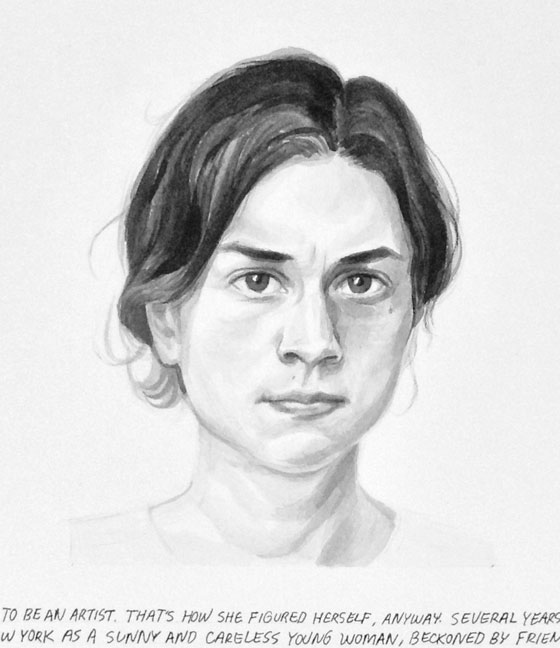

Olivia

Olivia used to be an artist. That’s how she figured herself, anyway. Several years ago she had come to New York as a sunny and careless young woman, beckoned by friends, whisperings, and the siren song of the City.

She made performance art in public spaces – starting with a small script or set of instructions, she could usually get people to talk to her or dance or listen briefly or laugh, and when done right, this work was cordial and humorous. It took the form of impromptu interviews, one-act plays, and curious games. Most of these were short-lived; some were sweet and revelatory and had Olivia walking away with a sense of positive impact.

As she vied for critical recognition, however, Olivia felt pressured to produce work that had teeth, or an intellectual rigor, or else an aesthetic brightness. But what could be done with work that, deliberately, had none of these qualities? Her art was soft and quiet and ephemeral and made of the same parts as normal life. She flirted with the use of costumes, but this felt ostentatious and chilled the average viewer.

After a while Olivia realized she didn’t need the formal restrictions of place or format to guide the performance; it could happen anywhere, in any situation. She fed it slowly into her everyday life. She talked with people waiting in line at the store, or on the subway stop, or in the hallway of her apartment building. But this game she played, the core of it at least, required no artifice, no put-on. It needed neither bite nor brightness because the thing she sought was simply a form of sincerity, an unconventional style of expression that ‘being an artist’ offered her, offered everyone. The rest of it she began to strip away. Where her artist friends had goals, proposals, motives, statements, she had what she had begun with: herself, and a love for people and their stories.

So she talked. She listened. But she did so without title or address, sans script, and lived her life artlessly. Maybe one day she would write a book about the people she had met, or find a reason to perform again. But for now she was content.